Firearms enthusiasts know well the series of events that transpire inside the brass case the moment the trigger is pulled, but let us review them for the sake of those that are not so familiar with powder burners: the firing pin impacts the primer, the pre-stressed mixture ignites, sending a jet of very hot gases through a small hole into the main/powder charge cavity of the case where the granules of smokeless or the flakes of black/synthetic powder ignite in a somewhat random fashion. The further high temperature and pressure of the gases defeat the coating of the granules and ignite them in somewhat of a chain reaction. This makes the pressure inside the case soar to levels that are high to really grasp in our normal everyday mind as we never encounter in our everyday lives things that work at between 16,000 and 55,000 pounds per square inch (PSI).

If you think Uncle Ted stepping on your toes was bad this last Christmas, I can assure you this would be many times worse.

The bullet is forced forward VERY rapidly. So rapidly that the front section of the bullet does not want to move and this forces the rear section of the bullet to expand into the rifling, sealing the gases behind. If the bullet is solid, there is little “upset” as this phenomenon is called, but if the bullet is hollow based or soft, this upset has to be taken into account when designing the bullet. Some is good, too much might not. For a short while, under these pressures and forces, the metal of the bullet is in almost a malleable/fluid state; and in a short time after this, the front of the bullet finally gets accelerated and also upsets, filling the rifling completely.

The exception, of course, are those barrels designed for military projectiles (where the potential of a government contract makes sense to go through the development process) and, to our knowledge, the 0.20" cal CCA barrel designed specifically for the JSB 13.7 grains Exacts (and made by Lothar Walther).

The MAIN duty of the rifling is to swage the projectile to its final shape and make it turn.

Why so many styles for such a simple duty? you may ask.

The reality is that the design of the rifling is also responsible for a number of things:

How much energy is needed to get that projectile swaged to its final shape?

How much interference there is between the original shape and the final shape and therefore, how much cleaning the barrel will need.

How UNIFORM can the barrel be built or made.

For a time, I experimented a bit with the Forsyth rifling (in airguns also known as the "Career" rifling. But that experiment, alas, was not as successful as I wanted. And yet it produced an interesting result (more on that later).

The saving grace is that, like some things in life nothing lasts forever, and this force is applied over a VERY short time to the pellet. So short that if you could apply the same proportion of force in a step in the same amount of time, you could walk on water. As a matter of fact, that is how some lizards actually walk on water.

So, the high pressure gas impinges on the pellet’s hollow skirt and drives forward the pellet. Just as in the case of the bullet, the pellet’s front section (the head) wants to stay put through inertia, and while the skirt is pushing forward, the head is resisting and this places all the stress in the waist or in the column that links the two parts (head and skirt) of the pellet.

As is the case in firearms, the high pressure gases also exert sideways forces and these tend to blow out the skirts of our pellets:

Once the pellet starts to move, depending on how the chamber was machined (or not), the head engages the rifling before the skirt and this also exerts a TORSIONAL stress on the waist or the column. At times, this stress may be enough to deform the pellet substantially, in most cases it is not, but it is still mentioned here to point out to problematic barrels that, in reality, need only to have their chambers fitted to the pellet the shooter wants to use.

In the case of the springer, when we release the trigger, the large mass of the piston gets accelerated forward, the seal seals when the pressure between the pellet’s resistance and the reducing chamber of the compression chamber reaches the point where the parachute opens (unless it is an ORing’ed piston). The piston continues to move not only due to the constant force applied by the mainspring, but also due to the inertia it has now acquired. By the time the piston reaches the end of the compression stroke, the pressure inside the compression chamber can be as high as 3,000 PSI’s and the TEMPERATURE can reach up to 2-3,000 F. Ideally, this set of conditions turn the air into a plasma and this plasma has very little internal friction (viscosity), so that it can flow through the transfer port and into the chamber.

Those shooters that have been shooting airguns for more than 15 years will remember the “Flying Trash Can” pellets, and how they sometimes blew up so badly as to become complete cylinders.

Luckily, the pellet making industry has advanced by leaps and bounds and we no longer have to worry with such extreme cases as long as we stick to quality ammunition and reasonable operating regimes. But it is still a concern where extreme precision is looked for with a spring-piston airgun, as paying attention to the internal ballistic aspects of the shot cycle is a must for those endeavours.

After the first, initial, blast starts expanding, the course of the pellet’s life inside the bore is pretty similar in either powerplant. The pellet will still travel through the bore and will still encounter the choke.

If you are a user/shooter:

Do note that the pellet designers have two basic ways of thinking. Let’s say, two “philosophies”:

In the case of JSB, H&N, RWS, and others, pellets are designed so that the head, USUALLY, rides the bore, but the SEAL is performed by the skirt at the groove. This allows for a little more efficiency from the system, as less energy is expended on re-shaping the hardest part of the pellet to the rifling.

It also implies that the skirt size needs to be closely matched to the GROOVE, depending on the specific design of the rifling. For example, if one rifle seems to be accurate with very large pellets (4.53’s or 5.55’s), then it MIGHT be worthwhile to test that rifle with pellets in the 4.50 or 5.51 sizes, as the difference is to make the head engage the rifling, or just ride on it.

So, each shooter has to decide what he wants to try and be prepared for behaviours that do not necessarily match pre-conceived notions of what 'should' work and what should not.

SOME guns may benefit, from the accuracy standpoint, of using one design style over another, BUT what is critical is that the consistency of the manufacturing demands is much higher when BOTH functions are assigned to one side of the pellet, as opposed to splitting the duties. On top of that, there will be a small efficiency drop, but a few fps is not important when you consider that the objectives of the airgunner are achieved through precision, not power.

If you ever get interested in designing a rifling.-

You need to define what "philosophy" you want to use: will your rifling engage the head fully all the way to the grooves? Will the rifling be designed to make the head "ride the lands" and only the skirt needs to seal? What rifling pitch will you use? What metal spec will you use to manufacture the barrels? Ordinary mild steel? What happens in the case of breakbarrels where the barrel is the cocking lever? Are you sure of the REAL, not the NOMINAL dimensions of the pellet you selected?

If, by some reason, you want it to shoot well ALL the pellets, by now it must be clear that such a magic barrel would be almost impossible.

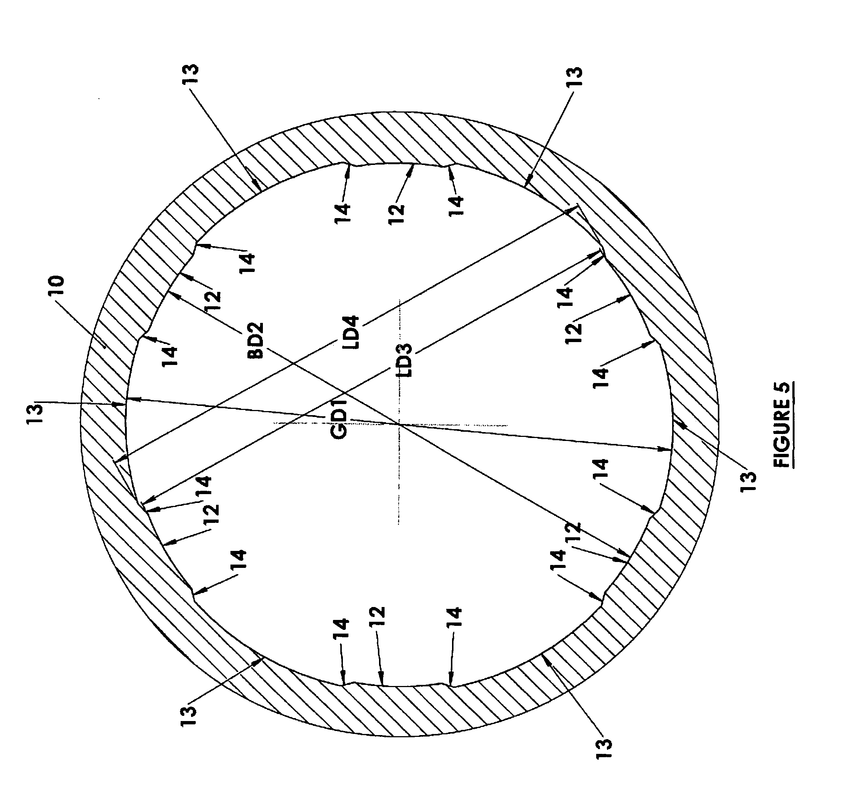

Just to give you an idea, here is a figure from a rifling patent, showing how many dimensions need to be specified for a rifling:

Now, all the theory in the world (even when proven by a few experiments) is useless in the field if in YOUR particular gun pellet ‘A’ shoots better than pellet ‘B’. So, ALWAYS test a number of pellets. ALWAYS keep an eye out for new introductions, ALWAYS keep an open mind as to what the future may bring, and ALWAYS remember that YOUR gun is really unique. It is up to YOU to discover what is BEST for you and your system.

Keep well and shoot straight!

RSS Feed

RSS Feed