And yet, it is true.

It is widely accepted that one of the premises of industrial production is the concept of "standard parts". I.E. parts that can be interchanged between assemblies and still maintain function of said assemblies; in a larger sense: parts that can be manufactured in large numbers by specialists, running special tools, jigs and gauges that allow them to ensure that the bunch of parts they make when assembled with the bunch of other parts that a bunch of other specialists like them have made, will produce a big bunch of assembled devices that work as intended. Enough to provide for an army.

Up until the 19th Century in the western world, all manufacturing was made by hand. Some parts were farmed out between different artisans and they each agreed on how to do things.

Large arms manufacturing regions grew up around this concept like Suhl and Styria in Europe, the Pennsylvania and Connecticut riflemaking areas in the USA and Tanegashima in Japan.

It is not uncommon in older guns (made between the 1400's and the 1800's) to find rifles that had one maker for the barrel, another for the lock and another for the stock. And that was good. It allowed for a number of independent makers to pool their resources to tackle a government contract. BUT there was also a downside: large parts were pretty much made all the same, or within certain practices and customs but, when even the screws had to be made by hand not all nuts screwed onto all screws! This created a peculiar situation where armies had real issues with maintenance.

Eli Whitney was the first western entrepreneur-politician to get the idea on the political map by getting Congress to give him money for the development of a standardized musket. The first successful demonstration of interchangeable parts to make long guns was done in front of a Congress committee in 1801 (the demonstration was rigged but), it allowed Whitney to get more funds and get the idea firmly rooted in the Industrial mind to the extent that it was from thereon, called the "American System".

By 1825 John Hall had implemented the idea of parts interchangeability and gauges for quality control at the Harper's Ferry Arsenal in Virginia.

It was not till just before the Mexican War (1846) that Joseph Whitworth in England standardized threads and screw sizes. By the Civil War, it was a common concept.

BUT, in the Far East, the idea of gauges, standard parts, standard metallurgy, and interchangeability had been born about 2,300 years before:

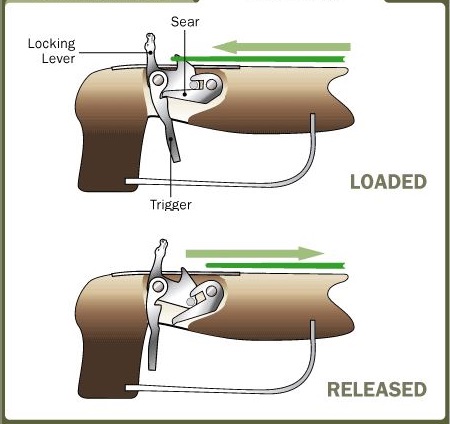

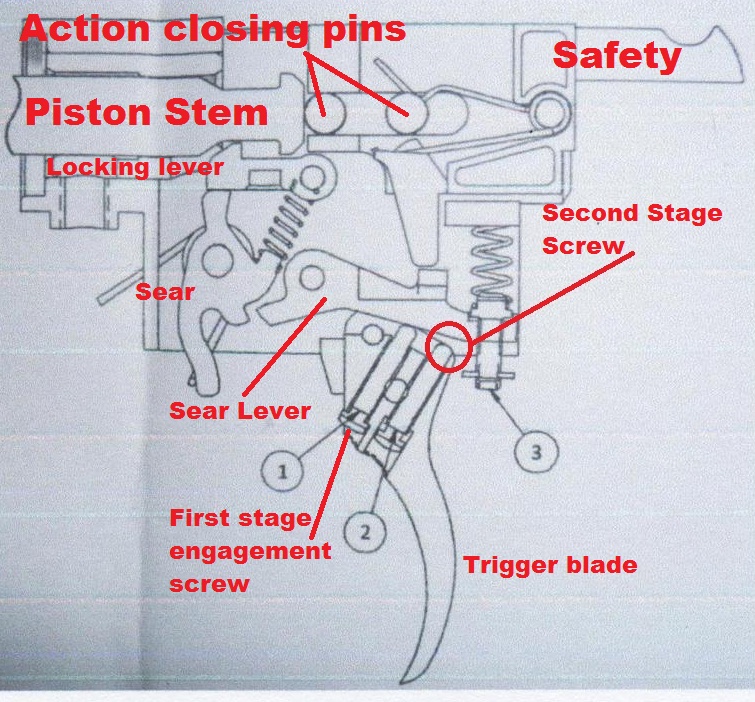

As the bowstring is drawn (or the piston's stem pushed back), the locking lever is raised by turning on its axle pin, which in turn raises a stationary pin at the front of the bottom lobe of the locking lever. This stationary pin then acts on the slot of the sear to bring it up. The trigger notch then can engage the sear and lock everything in place, until the trigger is pulled.

Those of you that are observant will ask ¿How is the trigger moved forward to engage the sear? there is no spring to do that!

And while they would be right, they are forgetting how a crossbow is cocked: USUALLY, the bow is fitted to a stock that has a nose, and that nose is set on the ground so that the shooter can pull the string with both hands, Therefore it is gravity what pulls the trigger "forward" (down in reality) when the sear and trigger notch get aligned.

Chinese crossbows had no butt section in the stock, that was invented in the middle east many years later (remember we are talking 500 BCE for the time being) and so the shooter took aim with the crossbow held in front of his eyes, held with both hands in the air.

In this position, the upper bar of the cocking lever aligned the eye and the point of the arrow, and if suitable markings were applied to the rear end of the cocking lever, it would also allow the firing officials to tell their soldiers how high to aim.

When you field thousands of crossbows you are not really interested in the accuracy of a single bolt, but you are rather more interested in an approximate DISTANCE to impact.

Military records show that the Chinese had perfected the "rising curtain" barrage and knew how to coordinate that with their cavalry charges. Not bad for a time when the Romans were still fighting in "turtle formation".

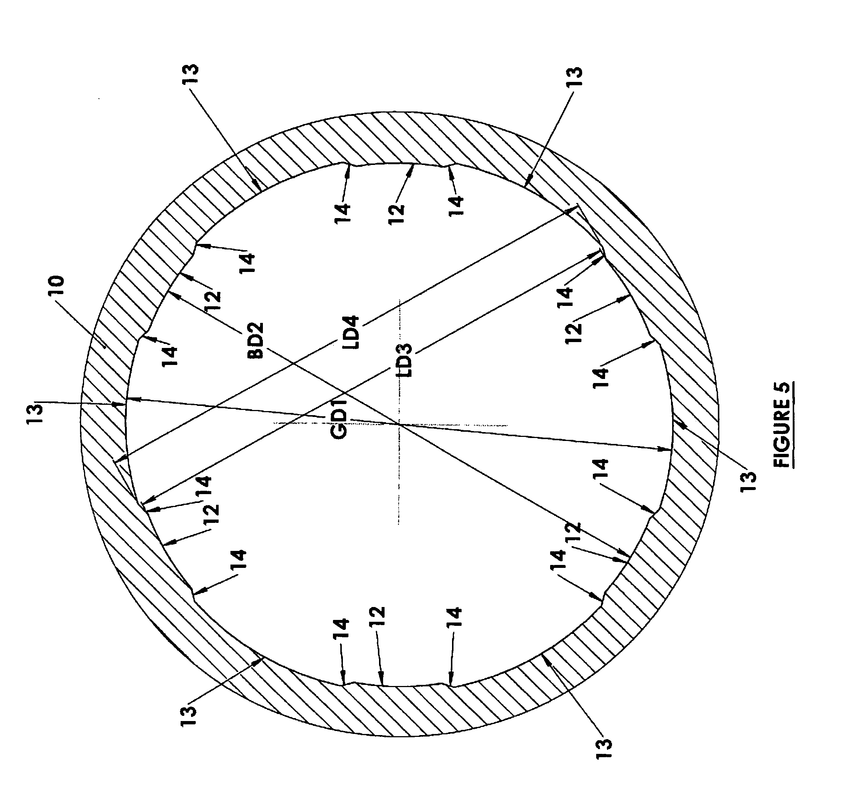

As time went by, the arrows became also more and more standardized, and then the bows. By the times of China's First Emperor (Shi-Huang-Ti of the western world's literature, roughly 210 BCE), things were pretty uniform, to the point where we can identify who made what in his tomb by the measurements of the pieces:

From there, it took another 773 years till single marksmen could make a dramatic impact in the course of human history, and another 200 years to get to the point where "surgical snipers" were a valued element of all armed forces.

¿What links the crossbow and the airgun as far as the triggers are concerned?

For one is the MAIN function: BOTH need to hold back rather impressive forces, while at the same time allowing for relatively smooth release of a well positioned (if not aimed) shot.

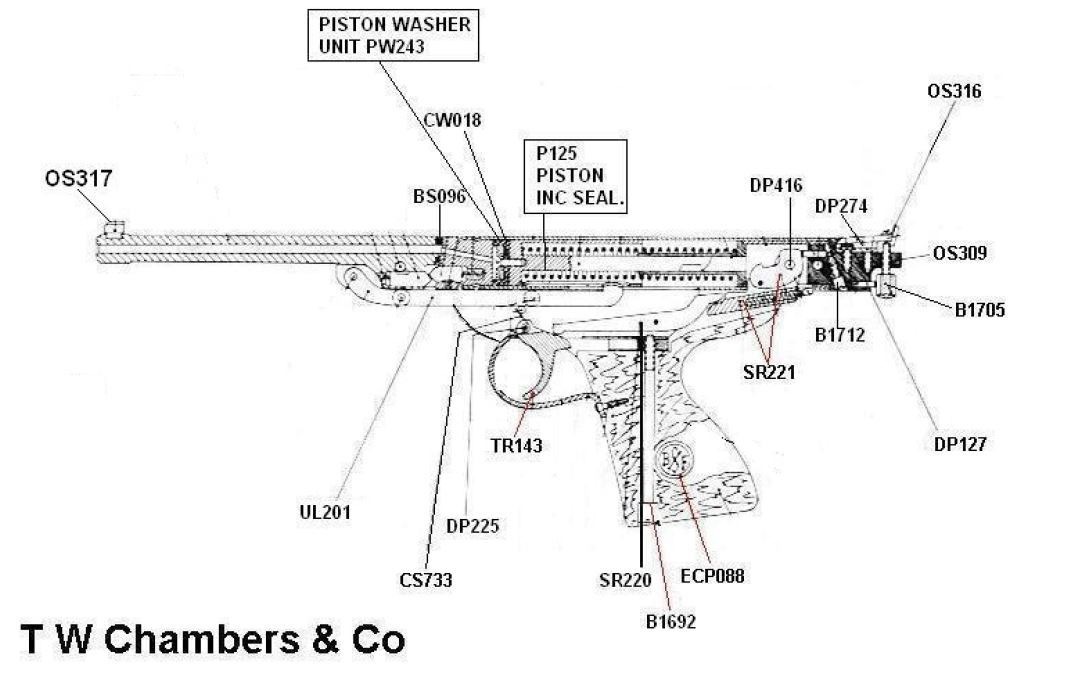

I do not know if modern airgun trigger designers had read, heard, or seen these examples. The Western crossbow trigger is radically different (and inferior IMHO) and yet, when you see the diagrams of the finest of the early airguns in modern times you cannot but see the resemblance:

Apart from the form, and basic functions, there is one more area where crossbow triggers also resemble most airgun triggers: It is the rearward motion of the string (or Piston Stem), what initiates the cocking action in the trigger.

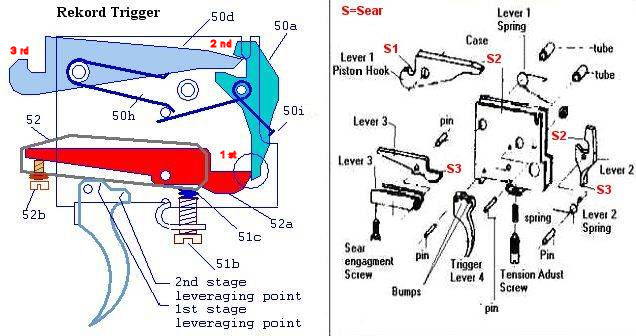

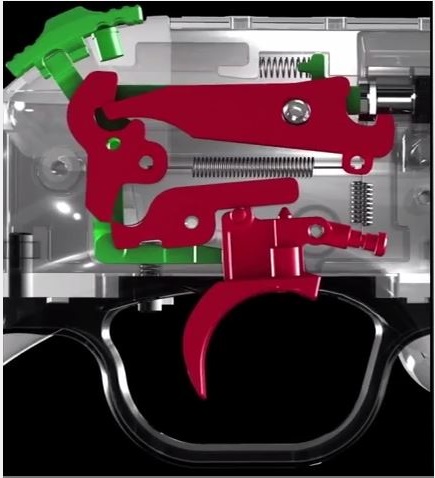

Let's look now at the Rekord trigger:

When the trigger pushes part 52a UP, that allows part 50a to move "back" and allows part 50d to release the piston to move forward.

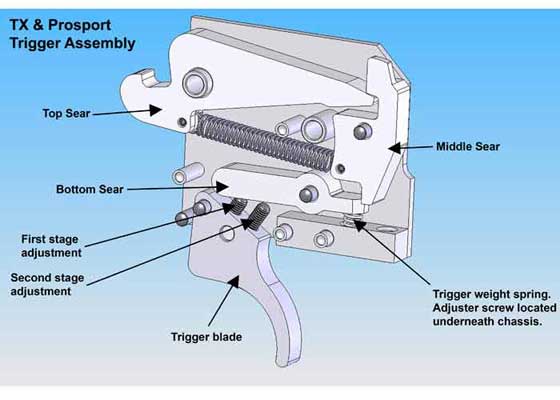

The TX-200 trigger is almost identical:

In all these triggers the SHAPE of the parts may be a little different, but in essence it is the same trigger.

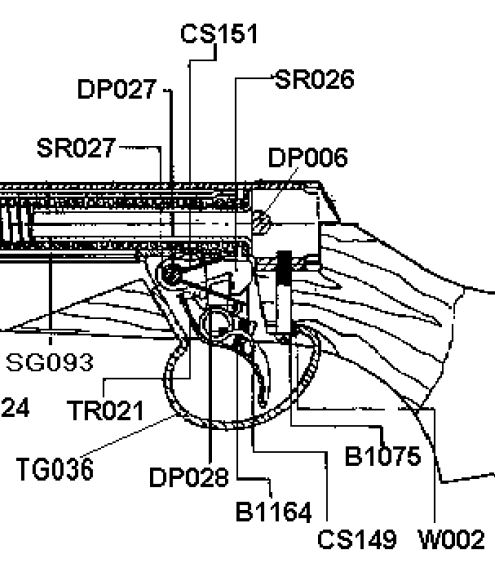

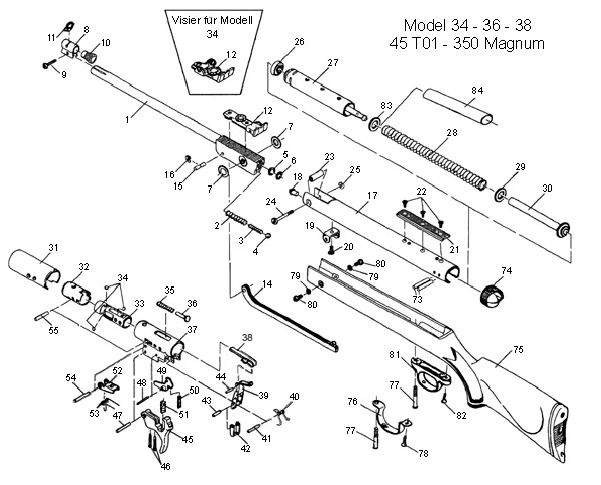

Diana, for reasons all of their own have never followed too closely the general trends in the rest of the airgun world, they started with the non-unitized triggers made up of loose parts but evolved into the unitized T-01 trigger shown here:

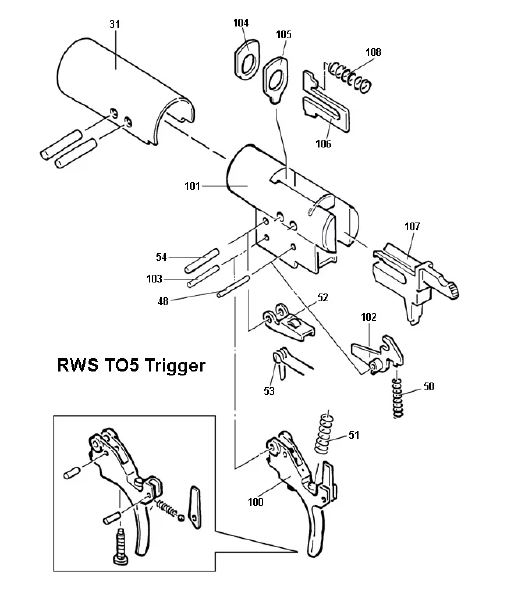

As is normal in companies, Diana developed new triggers that were numbered successively. The next major trigger was the T-05:

The T-05 CAN be made into a fine trigger, but it can never achieve the speed of release or the lightness of release that a Rekord/TX-200/LGV/LGU/Quattro. . . can achieve. The sliding plates simply take too much time in getting out of the way.

Enter the T-06 trigger:

It operates well from the start and it gets better with use. The parts that are REALLY under stress are hard steel castings and forgings. The process of fabrication itself yields parts that are tough cored and yet surface hard. Which is exactly what you want: inner strength and smoothly surfaced.

Seeing all the parts involved may frighten at first, but if we go to the core of the trigger, we see that we still have 3 basic levers interacting with each other to cock the rifle, and then release the spring.

Let's look at a simpler diagram:

The piston just needs to go past the hook to be latched/locked. The cocking of the trigger itself takes a lot less force than in the case of the typical airgun trigger.

Once the piston goes past the hook/locking lever, the sear engages and is blocked from allowing the hook to let go of the piston by the sear lever.

The sear lever is held in place by the spring and the trigger blade. As screw #1 is adjusted in, the degree of engagement of the first stage is set, and then the the additional force required to release the sear lever that then releases the sear is regulated by the second stage screw.

There is space in this trigger to add a true first stage travel regulation screw, but that is truly a job for a professional:

Selective additional parts, polishings and some tuning/changing of the screws will yield a trigger that is as good as any Match trigger. It has the speed to work well for offhand shots and the precision and repeatability for precision supported shots.

It CAN be made very light, but you really do NOT want too light a trigger. It is not only hard to control, but also VERY EMBARRASSING to loose points to a trigger that goes off with a thought.

A good trigger weight is around 1# give or take ½ of it. Some of us like triggers in the 2# region and with a good second stage because the "taking up" of the first stage is where we finish our mental preparation to release the shot.

Triggers have been advancing for almost 2,300 years, and we are lucky to be standing on the shoulders of giants. That first locksmith that designed the relatively complicated mechanism that performs all needed functions without hassle, day in day out; that will hold forces in the region of hundreds of pounds and, still, release those great forces with the exertion of a pound or two of our index fingers. Yes, if we can see far it is because we are standing on the shoulders of giants.

And so, next time that you are about to break a shot. Think for a moment about all those Chinese crossbowmen that enjoyed what in THEIR time was the epitome of the shooting art, and feel yourself in good company.

Keep well and shoot straight!

Héctor Medina

RSS Feed

RSS Feed